Raising a Fist

Protest ban flies in face of Olympic history

Months out from the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) published new guidelines for the games which completely ban any form of protest, with the committee explicitly forbidding signs, armbands, hand gestures and kneeling, though the document notes that these are not the only things that constitute protest.

The committee’s reasoning, as they put it, was to ensure positivity and unity in an increasingly divided world, and that by banning ethnic, religious or political protest, they could preserve this image.

The IOC, rightly so, has received fierce criticism from both media outlets and athletes themselves. Megan Rapinoe, a star of the American women’s soccer team, posted an image on social media vowing that she and her fellow athletes could not be silenced by such a move.

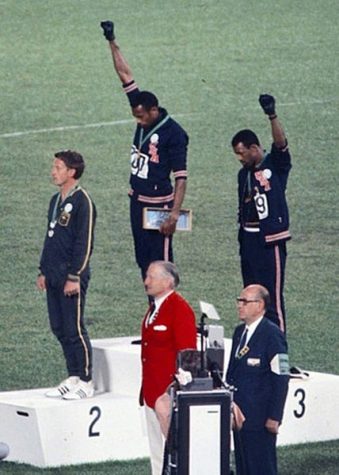

This action also flies in the face of Olympic history, which has routinely featured protests. Arguably the most famous is that of Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who at the 1968 games in Mexico City, each raised a gloved fist on the podium during the medal ceremony as the national anthem played (the pair had won gold and bronze, respectively).

The protest of Smith and Carlos was done to protest treatment of African-Americans, and, more broadly, in support of human rights (both men, along with Australian silver medalist Peter Norman, who supported the protest, wore human rights pins). It is worth noting that, at the same games, American boxer George Foreman took part in his own demonstration by waving a small American flag at the end of his match.

While also a demonstration, Foreman would receive no disciplinary action from the IOC. Smith and Carlos, on the other hand, were expelled from the Olympic village and would never compete at that level again.

While these protests have ingrained themselves in history, they are far from the only ones to occur, nor is it only Americans who have engaged in this. Vera Caslavska was a Czech gymnast who also engaged in protest at the 1968 games.

During her competition, there were questionable calls by judges, who changed previous scores for her Soviet opponent to place her ahead of Caslavska, but the primary reason for Caslavska’s ultimate protest was likely the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia earlier that year.

At the final medal ceremony, while the Soviet anthem played, Caslavska (the silver medalist) deliberately turned her head away from looking at the Soviet flag.

There are more cases, but these events from the 1968 Olympics demonstrate the point. The Olympics has always been a forum for expression and protest, and it goes against the history of the games for the IOC to declare there will be no protests.

And so, this raises the question. Why did the IOC make this decision?

At best, the committee made this decision because they genuinely do believe in the Olympics as an idyllic event that brings the world together, and that this should not be disrupted in any form. This is, obviously, a fantasyland. It neglects Olympic history.

The more likely scenario, from the perspective of an outside observer, is that the committee does not want to get in trouble for any protests competing athletes engage in.

If that more likely outcome is true, then the committee is nothing more than spineless cowards so concerned with their reputation that they attempt to micromanage the games and prevent anything tarnishing their precious image.

The National Olympic Committees of participating nations must apply pressure to the IOC to retract its decision and preserve the Olympics place as a respected event that allows free expression by its athletes.